Introduction

This conversation with comics creators Cole Pauls, Ho Che Anderson, and Dr. Candida Rifkind took place on October 16, 2021, as the second-day keynote for 80 Years and Beyond: A Virtual Symposium on Canadian Comics. This is an edited version of the conversation, which includes brilliant insights about Pauls’ and Anderson’s work, stylistic influences, and views on the state of the Canadian comics industry today.

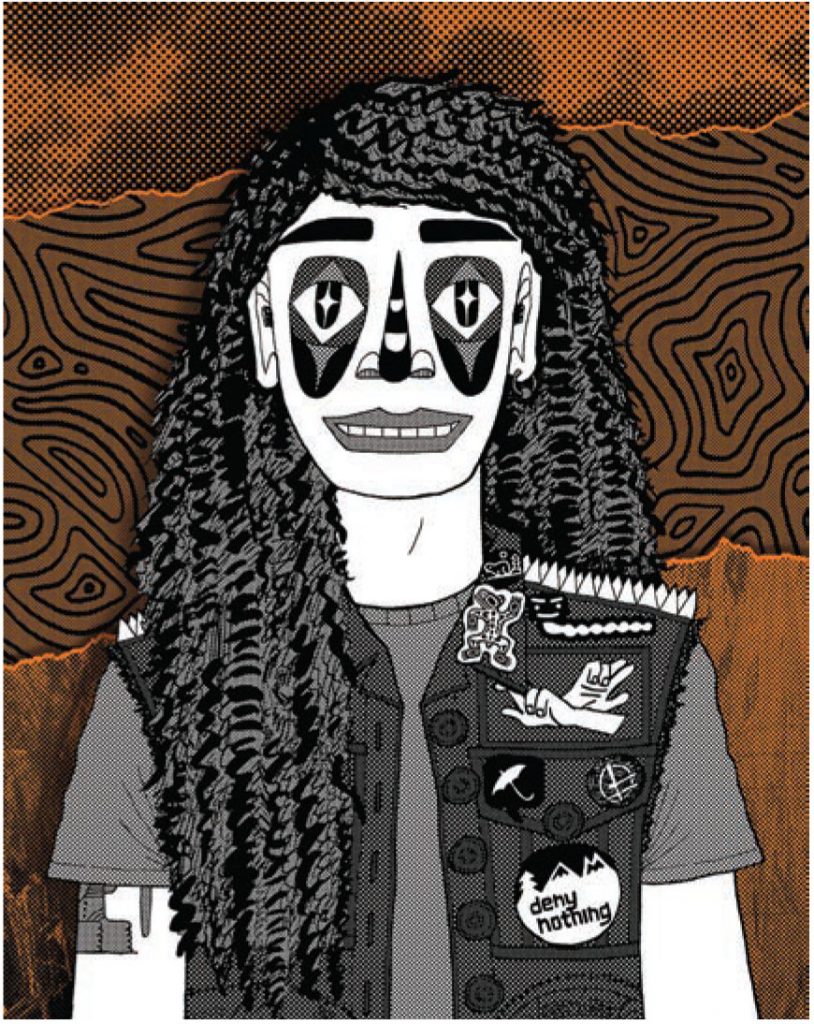

Self-Portrait of the artist, Cole Pauls. Reproduced with permission from Cole Pauls. (©Cole Pauls 2022)

The Conversation

Candida Rifkind: Cole, can you tell us about your breakout hit, Dakwäkãda Warriors, and how Southern Tutchone works in your comics?

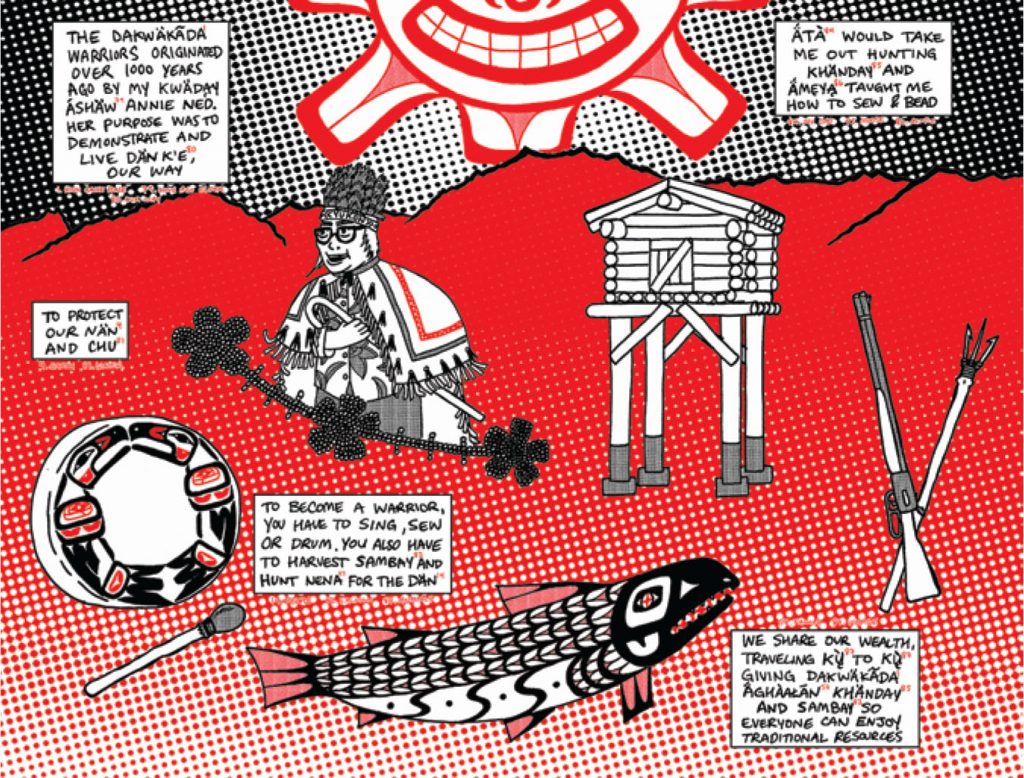

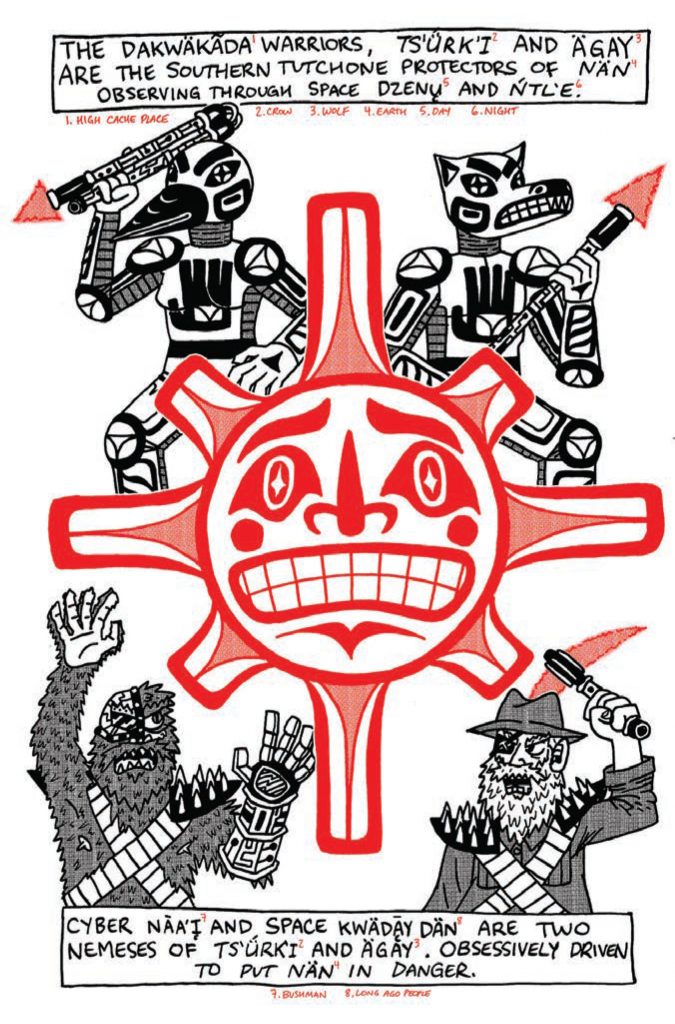

Cole Pauls: Dakwäkãda Warriors was my first graphic novel. It’s bilingual, so it has English and Southern Tutchone in it.1 It’s about Indigenous Power Rangers Wolf and Crow, who fight against evil pioneers and a cyborg sasquatch. I did three issues of it, and Conundrum Press released the collection two Septembers ago (2019).

I use a lot of Southern Tutchone in my comics to reclaim Indigenous space in the comics scene. There have been so many decades of misrepresentation of Indigenous people in all media but especially in comics, so finding ways to incorporate my hometown’s language into my work has been important to me. I often use resources from the Yukon Native Language Centre to help me with this, but I also have a couple of language preservers, Vivian Smith and Kershaw, that I can contact, as well.2 So, between the Internet and the people I can rely on, I write Southern Tutchone into all my comics.

CR: Have you been surprised by the success of Dakwäkãda Warriors?

CP: Oh, yeah. It’s been nice because while I really wrote it for Yukon youth, or maybe Yukoners in general, I think that the accessibility of the comic—how easy it is to pick it up and get a grasp of Yukon and Southern Tutchone culture—is what really boosted the popularity. It was drawn for Yukoners, but it’s not just for Yukoners if that makes sense.

CR: Ho Che, can you tell us a little bit about your style? Some people describe you as very cinematic, and of course, you are a filmmaker, as well. Can you give us a sense of how you feel your style has shifted over your career, or even over the course of King?

Ho Che Anderson: It’s kind of difficult to step outside of yourself and see your work objectively, but I have always had an attraction to cinematic language, and that has definitely leached its way into my comic book work. Although, as my career has gone forward in both streams, I’m less and less interested in applying cinematic techniques to my comics work. I’m more interested in exploring what is unique only to comic books and focusing on that. There’s no point to me any longer in cross-pollinating the two. But that’s definitely there in the foundation of my work, for sure. I’d have to describe my style as really kind of restless because I’ve always been attracted to stuff that is, for example, photo referenced, but also stuff that is entirely cartoony. I’m very attracted to work that is line based exclusively, but I also love picking up a brush and a tube of oil paint or acrylic paint and doing full-colour illustration.

There’s just such a broad variety of styles, techniques, and approaches to art. I’ve always wanted to kind of dabble a little bit in each of them, see if I can match them and wrangle them to my own ends as much as possible. But, if anything, my stuff tends towards a certain didacticism, and a certain dynamism. I’ve always been very attracted to, for example, Soviet propaganda art for its propagandistic nature and its ability to force an idea on you through dynamic image. But work that is more subtle is also really appealing to me, so I’m a little bit of a magpie stylistically.

CR: Cole, can you tell us a bit about your distinctive style? Where does it come from and what has influenced it?

CP: When I was fourteen, I took a trip down to Vancouver, and visited the Vancouver Art Gallery. It was on my way out, as I walked through the gift shop, that I discovered Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas’ Red: A Haida Manga had just come out, and it blew my mind because it was an Indigenous comic, a purely Indigenous comic.3 I had always wanted to see something like that, but I had also always wanted to make my own. So, seeing someone who had successfully done it really shaped my brain into being like, “Woah. I could do this too.”

From Dakwäkãda Warriors. Reproduced with permission from Cole Pauls. (©Cole Pauls 2019)

As for influences on my style, when I was a kid I was really into manga—Shonen Jump and stuff like that—so I find that I’m most confident in black and white. I think that, from the sheer amount of black-and-white comics that I’ve absorbed in my life, it’s kind of a crutch to me now. I make a drawing, I fill in the blacks, I add in some Zip-A-Tone, and then I consider it done. So, yeah, black-and-white comics are a big influence on me, too. And then, Gord Hill is also a huge influence on me, and he did a pin-up in the back of the Dakwäkãda Warriors book.

CR: When I look at your work as an outsider, I do see a kind of West Coast, Pacific Northwest Indigenous form line working there. Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas has also done really interesting things with bending the line and breaking the comics grid. Can you talk about your relationship to that iconic idea of what West Coast, Yukon, Tahltan, and Haida visual culture looks like?

CP: For Indigenous people, our art has a lot of story to it. We spoke our stories vocally, and I consider comics just another storytelling method. It’s kind of a big deal to call yourself a storyteller in my culture because then you’re like the keeper of knowledge and you have to master learning these legends and stories that you’re supposed to be able to retell in the perfect cadence. You have to meet a high standard to call yourself a storyteller. So, I guess I’ll still call myself a comics artist and, if my community calls me a storyteller, then I’ll accept it.

CR: Ho Che, there are very few Black Canadian cartoonists, but you’re certainly one of those groundbreaking creators depicting Black characters, Black lives, and Black political movements, like the Civil Rights movement. I asked Cole about being an Indigenous cartoonist, now I want to ask you about being a Black cartoonist in Canada.

HCA: Yeah, it’s a little bit of a lonely position, to be honest with you. When I started out, I couldn’t really point to anybody in this country that I was aware of that was doing the kind of stuff that I was doing. I didn’t have an experience like Cole had where I got to see a Black person in a comic book or know that a person of colour had created that work. The closest I got to that was the work of the Hernandez brothers, Mexican American cartoonists producing work that was very much about their culture in the 1980s in Los Angeles. That stuff was a real revelation to me. Aside from the brilliance of their cartooning, just the fact that they were a voice outside of the norm really galvanized me.

It was actually mostly in cinema that I got to see representations of people like myself through the work of Spike Lee, Charles Burnett, John Singleton, the list goes on. So that was more energizing to me. I was able to take that influence and put it into the work that I was doing in comic books at that time. That’s changed, fortunately, over the years; there are more female voices and people of colour who are doing their thing, so I can actually look to them as examples. But when I was starting out it was a lonely playing field, I can’t lie.

From Dakwäkãda Warriors. Reproduced with permission from Cole Pauls. (©Cole Pauls 2019)

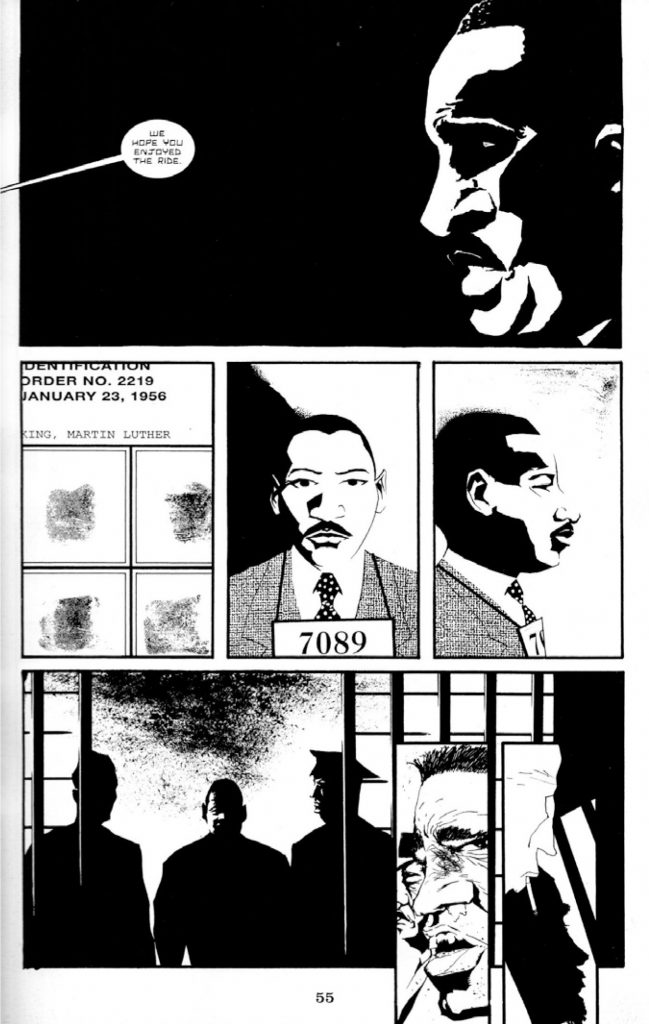

CR: I want to ask a question specifically about King—I know that you’ve published many other things—but I’d like to hear from you about that line between historical so-called fact and invention, creativity, and fiction. In King, you invent a female character to be there with the male leadership, which seems to be a feminist gesture that speaks to the under-explored historical role women played during that time, although the conventional ways that the story is told depict it as very much a masculine movement. So, what do you see as your responsibility in the telling of historical stories, when depicting real people, while balancing your artistic licence?

HCA: Well, I’ll tell you, I don’t know that I’d make that choice today. What I was trying to do was, as you say, reveal something about the prevailing depiction of the movement as male-dominated. The people who got the most coverage at the time, and even today, might have been the men, but so much of the work being done behind the scenes was by women. And so, lacking a recognizable female lead who could stand toe to toe with the guys, I thought, “Why don’t I just composite a bunch of different people and then create somebody who can be with them on the day-to-day.” And that worked out just fine for that time period, but I think if I were to tackle that book now, I would probably just have more female characters come in and out of the story—a series of real people as opposed to a composite character.

CR: Since its publication, have you heard from the King family or received any feedback from them about the book?

HCA: Initially. It was originally published in three volumes and, when the first volume came out, we heard from their estate. They were none too pleased. I think that’s because I wasn’t trying to do hagiography, but rather I was trying to be objective about who this person was. Families don’t always want you to be honest about the flaws of the person you’re doing a biography about; they often prefer you to just paint a rosy picture, which I can understand. But that’s not the game I was playing.

So, they were not too happy with us. They asked us to cease and desist, but we were kind of punk rock ourselves back then and just decided we were going to do what we had to do. At that time, I wasn’t concerned about lawsuits or legal ramifications of any kind, and my publisher followed suit. Today, we’re a little older, a little more conservative, so maybe if King were being published now, we might be a little bit more concerned about that, but I suspect not. The truth needs to be told, and if you have to suffer a few slings and arrows in the process then maybe it’s worth it.

From Ho Che Anderson’s King: The Special Edition (Fantagraphics, 2010).

CR: Cole, you’re in Vancouver and we tend to think of the Canadian comics scene as very Toronto-based, not least because of the TCAF, but also because we tend to always gravitate towards there.4 So, I was wondering how you see yourself within the Canadian comics scene as a Vancouver artist.

CP: Not living in Toronto, you see that a lot. For example, a new Canadian comics show will be announced and something like nine out of ten artists are Toronto-based artists, only leaving room for maybe one or two from the rest of the country. But, in terms of where I see myself, I would consider myself a Vancouver artist because I’ve lived here for almost nine years now. That said, my comics and subject matter are almost exclusively about the Yukon, and I definitely have a place back home too. So, I guess it’s both.

You know, a lot of people ask me what it is like being “the Yukon’s” comics artist, and I go, “Oh, well I’m not the artist, there’s a bunch of other people

there.” I guess that’s why we’re here; we’re here to celebrate other Canadian comics. And when people ask me that question, I always go, “Oh, do you know Chris Caldwell? Do you know Doug Urquhart? Do you know Kim Edgar, and Hecate Press out of Dawson City?”5 There’s a community of comic strip people in the North that hasn’t been discussed in Canadian comics, and they’re really good. Eventually, I’m going to do a big write-up about Northern representation and comics because I don’t feel like it’s discussed a lot.

CR: Ho Che, what do you think about the state of Canadian comics and the industry today?

HCA: I began my career in the 1980s right here in Toronto, working for a Canadian publisher called Vortex Comics.6 Publishing at the same time out of Montreal, and somewhere else in Canada, were Matrix Comics and Caliber Comics.7 So, there was a little bit of a homegrown industry. But what I really liked about Vortex Comics was the fact that they focused outside of the superhero genre, and they were more about the cutting edge of what was possible in comic books at that time. So, I came of age with the mindset that our talent and our publications didn’t have to take a backseat to anybody. That’s an attitude I have maintained ever since. We’ve produced cartoonists like Hal Foster, Todd McFarlane, Seth, Chester Brown, Ken Steacy, Julie Doucet, Paul Rivoche, Adrian Dingle, Ramón K. Pérez, Becca Kinsey, the list goes on and on. Our work is world class as far as I’m concerned.

Publishers like Drawn & Quarterly and Lev Gleason Presents (formerly known as Chapterhouse) have continued to set the high standard of publishing in Canada.8 It’s difficult to kind of look up from my computer or drawing board, as someone churning out work on a day-to-day basis, to take stock of the industry as a whole. I guess if I had to say anything, it would be that we’re in as good a place as we can expect to be with the behemoth that is the United States right below us. We will always have to deal with its size, but we’re never going to be less than what is produced down there. As far as I’m concerned, we produce the best cartoonists in the world and will continue to do so.

Notes

1. Southern Tutchone is “one of seven Athapaskan languages in the Yukon” and “is spoken in the southwestern part of the territory” (“Southern Tutchone”). There are several dialects of the language, each with their own distinct differences, but these differences do not prevent speakers of different dialects from understanding one another. “The language has a rich sound system,” with “seven vowels, three diphthongs, and four tones,” and “as many as 43 consonants” (“Southern Tuchtone”).

2. The Yukon Native Language Centre supports Yukon First Nations in language revitalization efforts through “training, capacity building, technical expertise, advocacy” and through acting as a central repository of language resources and training (Yukon). They believe that “[l]anguage learning is lifelong” and connected holistically “to cultural vitality, land, identity, health, and success in life.”

3. Red: A Haida Manga is a 2009 graphic novel by artist Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas. The full-colour, hand-painted graphic novel has been described as “a groundbreaking mix of Haida imagery and Japanese manga” and was nominated for both a Joe Shuster Award and a Doug Wright Award in 2010 (“Red”).

4. The Toronto Comics Art Festival (TCAF) “was founded in 2003” and “is an internationally acclaimed comic book festival held annually in Toronto” (“Our Story”).

5. Chris Caldwell is a Yukon artist whose satirical illustrations appear in Scenic Adventures in the Yukon Territory (2006). Doug Urquhart (1947-2015) was a Whitehorse biologist, environmentalist, and editorial cartoonist whose “PAWS” comic strip appeared in thirty-four Northern newspapers. “Kimberly Edgar is an awardwinning artist living on Tr’ondek Hwech’in land in so-called Dawson City, Yukon, Canada” (Kimberley Edgar). They have received multiple awards, including a Broken Pencil Zine Award, and have “been nominated for two Doug Wright Awards.” They are also the founder of Hecate Press, which works with artists from Northern Canada to build connections across circumpolar regions (Hecate Press).

6. Vortex Comics was “a Canadian independent comic book publisher” that operated from 1982 to 1994 “[u]nder the supervision of president, publisher, and editor Bill Marks” (“About”).

7. Matrix Graphic Series operated in Montreal, Quebec, from 1984 to 2002. Today, it is most notably recognized as the original publisher of John Bell’s Canuck Comics (1986), which is “the first major book on Canadian comics” (“Matrix”).

8. Drawn & Quarterly is an internationally renowned comics publisher operating out of Montreal, Quebec. Lev Gleason Presents began operation in 2020 by reviving the previously defunct Lev Gleason Publications, which had closed operations in 1956. Operating with four imprints, Lev Gleason Presents subsumed former Canadian comics publisher Chapterhouse Comics, and the Canadian characters associated with it (“Lev Gleason’s Legacy”).

Works Cited

“About: Vortex Comics.” DBpedia, dbpedia.org/page/Vortex_Comics. Accessed 11 Apr. 2022.

“A Brief History of Drawn & Quarterly.” Drawn & Quarterly, drawnandquarterly.com/about/. Accessed 11 Apr. 2022. Hecate Press, hecatepress.bigcartel.com/about. Accessed 11 Apr. 2022.

Kimberley Edgar: Illustrator, Visual Artist, Comic Book Artist, Maker, www.kimberlyedgar.com/about. Accessed 11 Apr. 2022.

“Lev Gleason’s Legacy Revived.” Lev Gleason: The Greatest Name in Comics, www.levgleason.com/about. Accessed 11 Apr. 2022.

“Matrix Graphic Series.” Grand Comics Database, www.comics.org/publisher/478/. Accessed 11 Apr. 2022.

“Our Story: About the Toronto Comics Art Festival.” Toronto Comic Arts Festival, www.torontocomics.com/about. Accessed 11 Apr. 2022.

“Red: A Haida Manga.” Douglas & McIntyre, douglas-mcintyre.com/products/9781771620222. Accessed 11 Apr. 2022.

“Southern Tuchtone.” Yukon Native Language Centre, www.ynlc.ca/languages/stutchone.html.

Yukon Native Language Centre. www.ynlc.ca/index.html.

Cole Pauls is a Tahltan comic artist, illustrator, and printmaker hailing from Haines Junction (Yukon Territory) with a BFA in Illustration from Emily Carr University. Residing in Vancouver, Pauls focuses on his two comics series, the first being Pizza Punks, a self-contained comic strip about punks eating pizza, and the other being Dakwäkãda Warriors. In 2017, Pauls won Broken Pencil Magazine’s Best Comic and Best Zine of the Year Award for Dakwäkãda Warriors II. In 2020, Dakwäkãda Warriors won Best Work in an Indigenous Language from the Indigenous Voices Awards and was nominated for the Doug Wright Award categories, The Egghead & The Nipper.

Ho Che Anderson is a Toronto artist and filmmaker who was born in London, England, and named after the Vietnamese and Cuban revolutionaries Ho Chi Minh and Che Guevara. Anderson began his career as the author of numerous graphic novels, including King, a biography of the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr.; the horror-thriller Sand & Fury; and the science fiction action-adventure Godhead. Anderson wrote and directed his first feature in 2018, the supernatural heist thriller Le Corbeau, for Canada’s Telefilm, and is currently in development on a second feature. He also recently directed his first animated short, Governance 2020, for the National Film Board of Canada. Next up is the supernatural graphic novel, The Resurrectionists, for Abrams Books imprint Megascope, and another NeoText novella, Rizzo, following his latest release, Stone.

Please note that works on the Canadian Literature website may not be the final versions as they appear in the journal, as additional editing may take place between the web and print versions. If you are quoting reviews, articles, and/or poems from the Canadian Literature website, please indicate the date of access.